Faster Charset Decoding

Recently I was doing some minor OpenJDK improvements around how we turn byte[]s into Strings - including removing the StringCoding.Result struct and reducing overhead of some legacy CharsetDecoders.

When experimenting in this area I stumbled upon a performance discrepancy: new String(bytes, charset) is often many times faster than creating the same String via an InputStreamReader, much more than seemed reasonable at first glance.

Analysing why and then optimizing as best I could led to some rather significant improvements.

TL;DR: Reusing a couple of intrinsic methods implemented to support JEP 254: Compact Strings, we were able to speed up ASCII-compatible CharsetDecoders by up to 10x on microbenchmarks. These optimizations should land in JDK 17.

Compact Strings

To understand what I did in depth we must trace the steps back a few years to the work to (re)introduce compact strings in JDK 9.

In JDK 8 String store its contents in a char[], plain and simple. But chars in Java are a 16-bit primitive, whose values map (roughly) to UTF-16. In much software many - or most - strings use only the lowest 7 (ASCII) or 8 (ISO-8859-1) bits, so we’re wasting roughly a byte per stored character.

Yes, there are locales where many common code points require more than 8 or even 16 bits in UTF-16, but the experience is that there’s a large number of ASCII-only strings in applications in almost any locale. Storing these in a more compact form would bring considerable footprint savings, especially if it comes at no - or little - cost for those strings that still need two or more bytes per character.

Using a more space-efficient representation had been considered and implemented before. JDK 6 had -XX:+UseCompressedStrings which changed String to use either a byte[] or a char[] transparently. That implementation was dropped before I started working on the OpenJDK, but I’ve been told it was a maintenance nightmare, known to degrade performance a lot when running applications with a significant share of non-ASCII Strings.

In JDK 9, a new attempt was conceived with Compact Strings, JEP 254. Rather than switching back and forth between a byte[] and a char[] as needed, String will now always be backed by a byte[] into which you map char values using a simple scheme:

- If all

chars can be represented by the ISO-8859-1 encoding: “compress” them and use 1byteperchar - Otherwise split all

chars into two bytes and store them back-to-back. Still effectively UTF-16 encoded

Add some logic to map back and forth and we’re done!

Well, while reducing footprint is great in and off itself, you also need to get performance just right.

It wouldn’t be very nice if the speed-up for strings that fit in ISO-8859-1 came at a major expense for strings requiring UTF-16 encoding. To alleviate such concerns JEP 254 turned out to be substantial effort. The integration lists 9 co-authors and 12 reviewers, and I’m sure there was involvement from even more engineers in QA etc.

Intrinsically fast

One way performance was optimized - in many cases over that of the JDK 8 baseline - was by implementing intrinsic methods for compressing char[]s to byte[]s, for inflating byte[]s to char[]s, etc.

Intrinsic methods in JDK parlance are Java methods which JVMs, such as OpenJDK HotSpot, may replace with highly-optimized, manually crafted methods. Such hand-optimization is a lot of work, but can ensure the JVM does the right thing in some very specific and highly performance-sensitive cases.

For the methods implemented in JEP 254, the main benefit is they allow for the tailored use of modern SIMD instructions. SIMD stands for Single Instruction, Multiple Data, and collectively describe hardware instructions that operate on many bits of data at once. For example Intel’s AVX2 extension can operate on 256 bits of data at once. Use of such instructions allow for great speed-ups in certain cases.

Deep Dive: new String(bytes, US_ASCII)

To see which SIMD instructions we might be running let’s take one of the simpler scenarios for a spin.

On a recent JDK new String(byte[], Charset) will do this when Charset is US_ASCII:

if (COMPACT_STRINGS && !StringCoding.hasNegatives(bytes, offset, length)) {

this.value = Arrays.copyOfRange(bytes, offset, offset + length);

this.coder = LATIN1;

} else {

byte[] dst = new byte[length << 1];

int dp = 0;

while (dp < length) {

int b = bytes[offset++];

StringUTF16.putChar(dst, dp++, (b >= 0) ? (char) b : REPL);

}

this.value = dst;

this.coder = UTF16;

}

The if-branch checks that CompactStrings is enabled, then calls out to StringCoding.hasNegatives:

@IntrinsicCandidate

public static boolean hasNegatives(byte[] ba, int off, int len) {

for (int i = off; i < off + len; i++) {

if (ba[i] < 0) {

return true;

}

}

return false;

}

This is a straightforward check that returns true if any value in the input is negative. If there are no negative bytes, the input is all ASCII and we can go ahead and copy the input into the String internal byte[].

Experimental setup

A simple but interesting scenario can be found in the readStringDirect JMH microbenchmark:

@Benchmark

public String readStringDirect() throws Exception {

return new String(bytes, cs);

}

To zoom in on the US-ASCII fast-path detailed above, I choose to run this benchmark with -p charsetName=US-ASCII -p length=4096.

My experimental setup is an aging Haswell-based Linux workstation. For Mac or Windows these instructions might need to be adapted - and results might differ on newer (or older) hardware.

I also made sure to prepare my JDKs with the hsdis shared library, which enables disassembling compiled methods with -XX:+PrintAssembly. (Though part of OpenJDK, for various licensing reasons builds of hsdis can’t be distributed. Here’s a great guide written by Gunnar Morling on how you can build it yourself if you can’t find a binary somewhere.)

I then run the microbenchmark with -prof perfasm. This excellent built-in profiler uses the Linux perf profiler along with data collected using -XX:+PrintAssembly to describe the hottest code regions the microbenchmark executes in very fine-grained detail.

Experimental Results

Scanning the profiler output for hot snippets of code then this one stood out as particularly hot:

│ 0x00007fef79146223: mov $0x80808080,%ebx

0.02% │ 0x00007fef79146228: vmovd %ebx,%xmm0

│ 0x00007fef7914622c: vpbroadcastd %xmm0,%ymm0

0.21% │↗ 0x00007fef79146231: vmovdqu (%rsi,%rcx,1),%ymm1

13.16% ││ 0x00007fef79146236: vptest %ymm0,%ymm1

11.34% ││ 0x00007fef7914623b: jne 0x00007fef791462a3

1.63% ││ 0x00007fef7914623d: add $0x20,%rcx

│╰ 0x00007fef79146241: jne 0x00007fef79146231

Yay, x86 assembly! Let’s try to break it down…

The first column indicates relative time spent executing each instruction. These values might skew a little hither or dither, but seeing more than 10% attributable to a single instruction is a rare sight.

The ASCII-art arrows in the second column indicates control flow transitions - such as the jump to the beginning of a loop. The third column lists addresses. The rest is the disassembled x86 assembler at each address.

The first three instructions prepare the 256-bit ymm0 vector register to contain the value 0x80 - repeated 32 times. This is done by loading 0x80808080 into xmm0 then broadcasting it with vpbroadcastd into each of the 32-bit segments of ymm0.

Why 0x80? 0x80 is an octet - or a byte - with the highest bit set. In Java a byte with the highest bit set will be negative. The value in ymm0 can thus be used as a mask that would detect if any of the bytes in another ymm register is negative.

And precisely this is what is done in the loop that follows:

vmovdqu (%rsi,%rcx,1),%ymm1)loads 32 bytes from the input array into theymm1register.vptest %ymm0,%ymm1performs a logical AND between the mask inymm0and the 32 bytes we just read.- If any of the bytes are negative, the next instruction -

jne- will exit the loop. - Otherwise skip forward 32 bytes in the input and repeat until

rcxis 0.

Not seen in this picture is the setup to ensure the value in rcx is a multiple of 32, and the handling of the up to 31 trailing bytes.

Ok, so we can see how the code we run takes advantage of AVX2 instructions. But how much does this contribute to the performance of the microbenchmark?

Benchmarking the effect of the intrinsic

As it happens intrinsics can be turned off. This allows us to compare performance with what C2 would give

us without the hand-crafted intrinsic. (One problem is figuring out what HotSpot calls these intrinsics; I had to grep through the OpenJDK source code to find that this one is identified by _hasNegatives):

Benchmark Score Error Units

readStringDirect 1005.956 ± 36.044 ns/op

-XX:+UnlockDiagnosticVMOptions -XX:DisableIntrinsic=_hasNegatives

readStringDirect 4296.533 ± 870.060 ns/op

The intrinsic vectorization of hasNegatives is responsible for a greater than 4x speed-up in this simple benchmark. Cool!

Enter the InputStreamReader

None of the above was fresh in my memory until recently. I wasn’t involved in JEP 254, unless “enthusiastic onlooker” counts. But as it happened, I recently started doing some related experiments to assess performance overhead of InputStreamReader. Motivated by a sneaking suspicion after seeing a bit too much of it in an application profile.

I conjured up something along these lines:

@Benchmark

public String readStringReader() throws Exception {

int len = new InputStreamReader(

new ByteArrayInputStream(bytes), cs).read(chars);

return new String(chars, 0, len);

}

This is a simple and synthetic microbenchmark that deliberately avoids I/O. Thus not very realistic since the point of InputStreams is usually dealing with I/O, but interesting nonetheless to gauge non-I/O overheads.

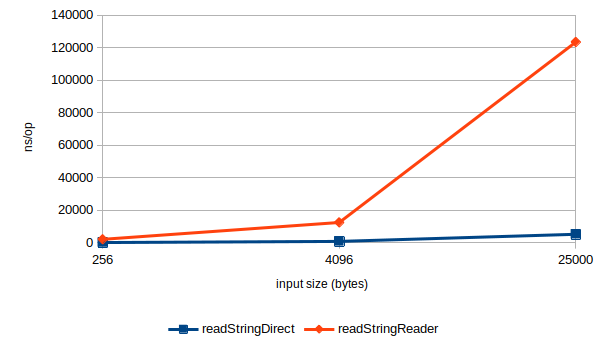

I also set up the readStringDirect benchmark I used in my experiment above as a baseline for this performance evaluation. I fully expected readStringReader to be a few times slower than readStringDirect: The InputStreamReader has to first decode the bytes read into chars, then compressing them back into bytes in the String constructor. But I was still surprised by the measured 12x difference:

Benchmark Score Error Units

readStringDirect 1005.956 ± 36.044 ns/op

readStringReader 12466.702 ± 747.116 ns/op

Analysis

A few experiments later it was clear that for smaller inputs readStringReader has a significant

constant overhead. Mainly from allocating a 8Kb byte[] used as an internal buffer. But it was also

clear the InputStreamReader might scale poorly, too:

When going from an input size of 4096 to 25000 - a factor of 6.1x - the readStringDirect

benchmark sees costs go up 6.5x. This is in line with what I’d expect: Almost linear, with small super-linear effects that could come from exceeding various cache thresholds. The readStringReader however sees costs go up 10x.

Digging into profiling data it was also clear that readStringReader spent most of the time in US_ASCII$Decoder.decodeArrayLoop copying bytes, one by one, from a byte[] to char[]:

while (sp < sl) {

byte b = sa[sp];

if (b >= 0) {

if (dp >= dl)

return CoderResult.OVERFLOW;

da[dp++] = (char)b;

sp++;

continue;

}

return CoderResult.malformedForLength(1);

}

Having several branches on the hot path is a red flag - and might be the reason for the super-linear costs adding up.

Reuseable intrinsics

The solution feels obvious in hindsight: copying from byte[] to char[] was one of

the things JEP 254 had to spend a lot of effort optimizing to ensure good performance.

Reusing those intrinsics seem like a no-brainer once it dawned upon me that it was actually feasible.

To keep things clean and minimize the leakage of implementation details I ended up with a PR that exposed only two internal java.lang methods for use by the decoders in sun.nio.cs:

decodeASCII, which takes an inputbyte[]and an outputchar[]and decodes as much as possible. For efficiency and simplicify implemented using a new package private method inString:

static int decodeASCII(byte[] sa, int sp, char[] da, int dp, int len) {

if (!StringCoding.hasNegatives(sa, sp, len)) {

StringLatin1.inflate(sa, sp, da, dp, len);

return len;

} else {

int start = sp;

int end = sp + len;

while (sp < end && sa[sp] >= 0) {

da[dp++] = (char) sa[sp++];

}

return sp - start;

}

}

inflateBytesToChars, which exposes theStringLatin1.inflateintrinsic method as is, for use by theISO_8859_1$Decoderin particular.

The while-loop in US_ASCII$Decoder.decodeArrayLoop could then be rewritten like this:

int n = JLA.decodeASCII(sa, sp, da, dp, Math.min(sl - sp, dl - dp));

sp += n;

dp += n;

src.position(sp - soff);

dst.position(dp - doff);

if (sp < sl) {

if (dp >= dl) {

return CoderResult.OVERFLOW;

}

return CoderResult.malformedForLength(1);

}

return CoderResult.UNDERFLOW;

Same semantics, but the bulk of the work will be delegated to the decodeASCII method, which should unlock some speed-ups thanks to the SIMD intrinsics.

Results

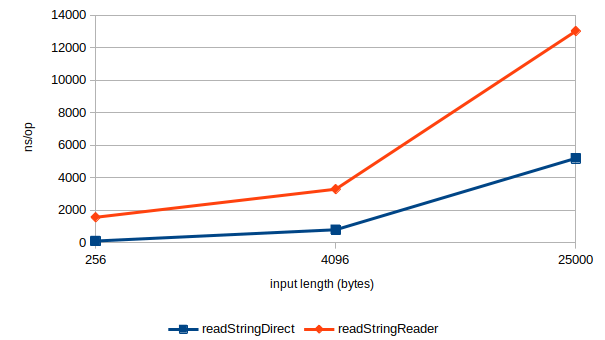

Plotting the same graph as before with the optimized version paints a wholly different image:

Taking the constant overhead of the InputStreamReader into account, readStringReader now trails readStringDirect by roughly a factor of 2.2x, and exhibits similar scaling.

At the 25000 input length data point the optimization sped things up by almost a factor of 10 for US-ASCII. In the aforementioned PR - which has now been integrated - I sought to improve every applicable built-in CharsetDecoder. Perhaps less work than it sounds since many of them inherit from a few base types that could be optimized. The result is many charset decoders can take this intrinsified fast-path when reading ASCII.

Before:

Benchmark (charsetName) (length) Cnt Score Error Units

readStringReader US-ASCII 256 10 2085.399 ± 66.522 ns/op

readStringReader US-ASCII 4096 10 12466.702 ± 747.116 ns/op

readStringReader US-ASCII 25000 10 123508.987 ± 3583.345 ns/op

readStringReader ISO-8859-1 256 10 1894.185 ± 51.772 ns/op

readStringReader ISO-8859-1 4096 10 8117.404 ± 594.708 ns/op

readStringReader ISO-8859-1 25000 10 99409.792 ± 28308.936 ns/op

readStringReader UTF-8 256 10 2090.337 ± 56.500 ns/op

readStringReader UTF-8 4096 10 11698.221 ± 898.910 ns/op

readStringReader UTF-8 25000 10 66568.987 ± 4204.361 ns/op

readStringReader ISO-8859-6 256 10 3061.130 ± 120.132 ns/op

readStringReader ISO-8859-6 4096 10 24623.494 ± 1916.362 ns/op

readStringReader ISO-8859-6 25000 10 139138.140 ± 7109.636 ns/op

readStringReader MS932 256 10 2612.535 ± 98.638 ns/op

readStringReader MS932 4096 10 18843.438 ± 1767.822 ns/op

readStringReader MS932 25000 10 119923.997 ± 18560.065 ns/op

After:

Benchmark (charsetName) (length) Cnt Score Error Units

readStringReader US-ASCII 256 10 1556.588 ± 37.083 ns/op

readStringReader US-ASCII 4096 10 3290.627 ± 125.327 ns/op

readStringReader US-ASCII 25000 10 13118.794 ± 597.086 ns/op

readStringReader ISO-8859-1 256 10 1525.460 ± 36.510 ns/op

readStringReader ISO-8859-1 4096 10 3051.887 ± 113.036 ns/op

readStringReader ISO-8859-1 25000 10 11401.228 ± 563.124 ns/op

readStringReader UTF-8 256 10 1596.878 ± 43.824 ns/op

readStringReader UTF-8 4096 10 3349.961 ± 119.278 ns/op

readStringReader UTF-8 25000 10 13273.403 ± 591.600 ns/op

readStringReader ISO-8859-6 256 10 1602.328 ± 44.092 ns/op

readStringReader ISO-8859-6 4096 10 3403.312 ± 107.516 ns/op

readStringReader ISO-8859-6 25000 10 13163.468 ± 709.642 ns/op

readStringReader MS932 256 10 1602.837 ± 32.021 ns/op

readStringReader MS932 4096 10 3379.439 ± 87.716 ns/op

readStringReader MS932 25000 10 13376.980 ± 669.983 ns/op

Note that UTF-8 - perhaps one of the most widely used encodings today - already had an ASCII fast-path in its decoder implementation. This fast-path avoids some branches and seems to scale better than the other charset decoders: a 6.5x cost factor going from 4096 to 25000 inputs after discounting the constant overheads. But even UTF-8 also saw significant improvements on my system by reusing the intrinsics. Almost 5x on 25000 byte inputs.

In the end, in this particular micro, improvements range from 1.3x for small inputs to upwards of 10x for larger inputs.

I added a number of other microbenchmarks to explore how the microbenchmarks behave when adding in non-ASCII characters in the inputs, either at the start, end or mixed into the input: before / after. Performance in the *Reader micros now mostly mirror the behavior of the *Direct micros, with a few exceptions where the Reader variants actually perform better thanks to processing the input in 8Kb chunks.

There are likely ways to improve the code further, especially when dealing with mixed input: when decoding into a char[] turning String.decodeASCII into an intrinsic that fuses hasNegatives + inflate could makes sense since we don’t really have to bail out and restart when we find a negative byte. But this enhancement is great progress already, so I have resisted the temptation to reach for an additional gain. At least until the dust has settled a bit.

Real world implications?

One user approached me about testing this out in one of their application, since they had seen heavy use

of decodeArrayLoop in their profiles. After building the OpenJDK PR from source, they could test out the

patch before it was even integrated - and reported back reductions in total CPU use around 15-25%!

But… it turned out I/O was often the bottleneck in their setup. So while CPU savings were significant those didn’t translate into a throughput improvement in many of their tests. YMMV: Not all I/O is shaped the same way, and the optimization could have positive effects on latency.

In the end I think the user in question seemed quite happy with the CPU reduction alone, even if it didn’t improve their throughput much. If nothing else this should translate into power and cost savings.

Acknowledgements

I’d like to especially thank Tobias Hartmann for helping out with many of the questions I had when writing this post. I also owe a debt of gratitude to him alongside Vivek Deshpande, Vladimir Kozlov, and Sandhya Viswanathan for their excellent work on these HotSpot intrinsics that I here was merely able to leverage in a few new places. Also thanks to Alan Bateman and Naoto Sato for reviewing, discussing and helping get the PR integrated, and to David Delabassee for a lot of editorial suggestions.

Appendix: Internals of a C2 intrinsic

I was curious to find out if my reading of the disassembly made sense, but couldn’t find my way around. The C2 code is tricky to find your way around, mainly due heavy reliance on code generation, but Tobias Hartmann - who I believe wrote much of this particular intrinsic - was kind enough to point me to the right place: C2_MacroAssembler::has_negatives.

This is the routine that emits x86 assembler custom-built to execute this particular piece of Java code as quickly as possible on the hardware at hand. If you studied that code you’d find the macro assembler used to emit the hot piece code I found when profiling above at line 3408:

movl(tmp1, 0x80808080); // create mask to test for Unicode chars in vector

movdl(vec2, tmp1);

vpbroadcastd(vec2, vec2, Assembler::AVX_256bit);

bind(COMPARE_WIDE_VECTORS);

vmovdqu(vec1, Address(ary1, len, Address::times_1));

vptest(vec1, vec2);

jccb(Assembler::notZero, TRUE_LABEL);

addptr(len, 32);

jcc(Assembler::notZero, COMPARE_WIDE_VECTORS);

Not without its’ quirks, but a bit more higher level and somewhat readable.